By Brenda S. Cox

“A few months had seen the beginning and the end of their acquaintance; but, not with a few months ended Anne’s share of suffering from it.”–Persuasion

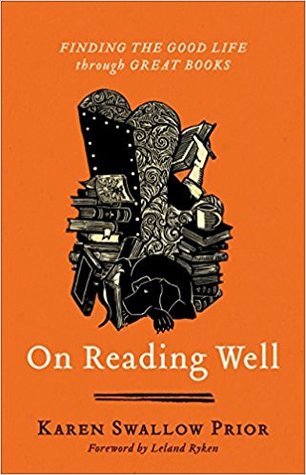

When you think of Anne Elliot of Persuasion, what virtue comes to mind? Karen Swallow Prior, in her book On Reading Well, considers Anne the quintessential example of patience.

Suffering and Patience

Prior defines patience as “the willingness to endure suffering.” (We also use the word patient for someone suffering from an illness.) We all face suffering at times. We might choose to respond with anger, or, at the other end of the spectrum, with passiveness or fatalism. Or, we might endure patiently, as Anne Elliot does in her suffering.

Anne suffers deeply from her loss of Captain Wentworth, then from watching him flirt with the Musgrove girls when he returns. She also suffers from her family, who openly treat her with contempt. No one considers her wants or needs. For example, in chapter 2,

“the usual fate of Anne attended her, in having something very opposite from her inclination fixed on. She disliked Bath, and did not think it agreed with her–and Bath was to be her home.”

Anne’s Patience

However, in her suffering, Anne does not wallow in self-pity or yield to depression. Nor does she angrily lash out. Instead, she patiently continues doing what she knows is right. She treats her father respectfully and cares for the family’s tenants. She cheers up her fretful sister, and listens to, and makes peace between, family members.

In Lyme, she recognizes Captain Benwick, who has lost his fiancée, as a fellow sufferer. She patiently listens to him, drawing him out. And she teaches him “the duty and benefit of struggling against affliction”—something she knows very personally.

Anne’s Advice

Benwick has been wallowing in poetry that intensifies his feelings (much as Marianne Dashwood indulges her emotions). Anne recommends that instead he read

“such works of our best moralists,

such collections of the finest letters,

such memoirs of characters of worth and suffering,

as occurred to her at the moment as calculated

to rouse and fortify the mind

by the highest precepts,

and the strongest examples of moral and religious endurances.”

In other words, he should read the stories of people who have faced suffering and not let it control them, but continued to do what was right. Anne no doubt is very familiar with such works, which must have helped her in her own “struggle against affliction.”

The duty to patiently endure suffering is identified as “moral and religious”; for Anne (as for Austen), it was her duty as a Christian to be patient under affliction.

She thinks, however, that she is not living up to what she has preached to Benwick.

“Anne could not but be amused at the idea of her coming to Lyme, to preach patience and resignation to a young man whom she had never seen before; nor could she help fearing, on more serious reflection, that, like many other great moralists and preachers, she had been eloquent on a point in which her own conduct would ill bear examination.”

She doesn’t recognize her own valor in bearing her suffering well, without grumbling or self-centeredness.

Anne’s years of practice in recognizing her painful feelings, but not letting them control her, pay off. When Louisa is injured, Anne overcomes her distress and rationally organizes the help Louisa needs.

Conscience and Duty

Anne also has a clear conscience to sustain her in her suffering. When she considers having yielded to Lady Russell’s persuasion, she says, “I must believe that I was right, much as I suffered from it.” She did her duty (a word with religious connotations, her Christian duty) in submitting to a woman who stood in the place of a mother to her. She adds, “a strong sense of duty is no bad part of a woman’s portion.” (Of course, a sense of duty was also essential for men, especially military men like Wentworth.)

As in Austen’s other novels, the practice of Christian virtue requires self-knowledge. In Anne’s years of suffering, she has learned to know herself well. She is constantly thinking, evaluating, and choosing her reactions and her path.

Austen’s Novels

Prior asserts that even the form of Austen’s novels, which use irony and satire, helps readers grow in patience. Patience requires us to see the points of view of others, not just think of our own desires. Similarly, irony requires readers to identify two layers of meaning—what is being said, and what is meant (which in irony is the opposite of the stated meaning). This helps us expand our view of the world. And satire’s purpose is to point out issues so that we will try to correct them, making the world better.

The Other Virtues

Karen Swallow Prior’s On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books discusses twelve Christian virtues: Prudence, Temperance, Justice, Courage, Faith, Hope, Love, Chastity, Diligence, Patience, Kindness, and Humility. For each, she examines traditional Christian understandings of that virtue, then shows it in a classic story or novel.

Besides Persuasion, Prior includes books Austen probably read: Henry Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones as an example of prudence, and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress for diligence. She also uses other books most of us have read, like Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn for courage. Faith is illustrated by Shusako Endo’s Silence, a fascinating and disturbing story of the persecution of Christians in Japan. Other stories were unfamiliar to me, including George Saunders’ “Tenth of December” on kindness; for those, she explained the story thoroughly enough that I could still understand the main points.

This is a serious book, not light reading. But I found it fascinating to see literary classics in a new light. And I enjoyed being introduced to new works as well. The book is available on kindle unlimited.

Prior claims that Anne Elliot is Austen’s most lovable and most admirable character. Others, such as Elizabeth Bennet, are lovable, but not as admirable. Some, such as Fanny Price and Elinor Dashwood, are admirable, but not as lovable. Do you think it is difficult to be both lovable and admirable? Which of Austen’s characters do you think best exemplify the virtues listed above?

Patience does seem the outstanding virtue of Anne Elliot. Maybe the behavior that stands out is her listening to others–which of course requires patience.

And I do see her as both lovable/admirable, though her family cannot see it.

On Reading Well is going on my TBR!

LikeLike

Good point, Kevin; listening is definitely one of Anne’s strengths! I hope you’ll enjoy the book. 🙂

LikeLike