By Brenda S. Cox

“We are all trying to make our way in the world. Some of us are guided by what we think of ourselves, others by what others think of us.”—Elinor, in the new Hallmark adaptation of Sense and Sensibility

Most Janeites would agree that Jane Austen’s novels are “practically perfect in every way.” And for some people, that’s enough. We can just keep re-reading the novels, seeing new aspects and messages each time. And we read nonfiction that tells us more about Austen, her world, and her writings from new angles.

Novels

However, Austen only wrote six full novels (unless you count Lady Susan, which is more of a novella). And so, for others of us, the novels lead us to want more. We read prequels and sequels and the stories from different points of view. Other variations explore “what if’s” that take us in different directions and set the stories in other times and places. Most of these have focused on Pride and Prejudice, but all the other novels have been adapted as well.

A search on Amazon shows 25-30 novels based on Sense and Sensibility. (There are thousands of variations of Pride and Prejudice, I think.) Of the handful I’ve read, my favorite is Colonel Brandon in His Own Words, by Shannon Winslow. That gave me a greater appreciation of Colonel Brandon, whom Austen doesn’t develop quite as much as I’d like.

Plays

I don’t often get the chance to see theatrical Jane Austen adaptations, but I usually enjoy them very much. It’s fun to be in an audience of other Austen-lovers, laughing together, discussing the play during intermission and after, and feeling the actors are acting for us personally.

I imagine that adapting for the theater has many challenges. As with movies, time limitations mean many parts of the story have to be left out. The number of actors is likely more limited in the theatre. Of course you can’t have the beautiful scenery and fancy homes used in movie productions; the audience has to use their imagination more.

Kate Hamill wrote a delightful stage version of Sense and Sensibility, which I got to see after the JASNA AGM in Williamsburg. With a simple set and “gossips” to catch us up on narration, the play provides humor, dancing and music, and lots of fun. (I recently watched Kate Hamill’s stage version of Pride and Prejudice, which is also well done.)

I also once saw an outdoor production of Sense and Sensibility in England. What I mainly remember is that it was raining for about half the play, but the audience sat on chairs or blankets on the wet grass and used their umbrellas. The show went on, and we had a good time. I guess in England you just ignore the rain if you possibly can.

Last night I saw a new version of Sense and Sensibility at Atlanta’s Shakespeare Tavern, a place I usually love. The play, written by Claire F. Martin, was produced by Belle Esprit, with color-blind casting. While the three sisters were played by individual actors, the other five actors each played three characters. That was sometimes confusing. For example, when one particular actor came out, it always took me a while to figure out if he was Robert Ferrars, Sir John Middleton, or Willoughby. The play was lively and energetic, entertaining and sometimes funny, though not terribly consistent with Austen’s novel.

Austen adaptations often help me to focus on new aspects of the novel. This one emphasized, surprisingly, that Elinor was a liar. In the novel, Elinor is shown as the most upright of the characters, always doing her duty to love her neighbours as herself. However, apparently to these modern performers, the fact that Elinor does not always express her feelings, but tones them down, makes her a liar. I disagree on that point. Elinor works hard to keep her feelings “under good regulation,” and she carefully keeps her word when it comes to secrets.

Actress Lucy Taylor wrote, in Jane Austen: Antipodean Views, that the “restraint” in Austen’s novels is “actually quite like acting. It’s far more interesting to watch a character attempt to suppress their emotions, than simply expressing them. The result is often a performance that is complex and delicate.”

This particular stage version included little of that restraint. There were no real secrets. And nothing was toned down. It was something of a farce, full of exaggerations. Mrs. Middleton, for example, played by a man, is excessively paranoid of illness, like Mr. Woodhouse of Emma. Margaret and Marianne are hoydens who shout at each other and at other people. I could sympathize with Fanny Dashwood for throwing them out of Norland Park, since they were so obnoxious and openly rude to her. Elinor didn’t shout, but she scolded and looked sad or scowling much of the time, which made it hard to see why Edward liked her.

I did enjoy hearing passages from a Fanny Burney novel read aloud and connected to the plot. That was interesting, though difficult to follow. A stated goal of Belle Esprit is to place “a feminist lens on history,” and this is clear in the play. It included several negative remarks about men. Margaret said, as she was reading the Burney novel, that women should marry women (not a popular 19th century opinion, nor likely to have been Burney’s or Austen’s view).

Margaret took a very active role in this adaptation, which was interesting (though in reality she would not have been allowed to go to balls and shout at people, or to write letters to unrelated men). She has only a minor role in the novel. Of course the Emma Thompson movie version added to that by giving her a special connection with Edward. Most later variations have continued to give Margaret a more active role, this one the most I’ve seen.

I would not recommend this play for families with children. Characters used a lot of bad language, which is quite jarring in a Jane Austen play. This was on the order of “What the hell is she doing here?” Also, Willoughby is blatantly out to seduce Marianne, though the actual seduction happens off-stage, thankfully. She does not experience consequences and is not repentant; very different from the Marianne of the novel who is repentant even for lesser sins.

Overall, this play was an interesting perspective on Sense and Sensibility, but I wouldn’t choose to watch it again. I prefer versions that are closer to the original values, style, and language.

Movies

A variety of movie versions of Sense and Sensibility have come out; JASNA lists them here. The films make various choices on which minor characters to leave out (i.e. Margaret Dashwood or Lady Middleton), where to set the action, and what explanations to add in.

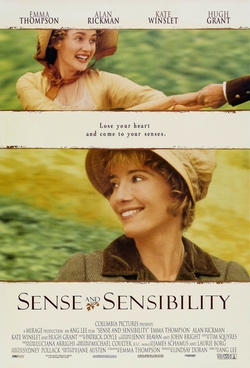

My personal favorite is the 1995 version with Emma Thompson (who played Elinor and wrote the screenplay), Kate Winslet, Hugh Grant, and Alan Rickman. Thompson won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

While including most of the story, Thompson expands the roles of Margaret, Edward, and Colonel Brandon, fleshing out those characters without breaking the rules of the society they lived in. Elinor’s self-control and Marianne’s lack of it are clear to see. We have some focus on the restricted roles and choices of women: themes in Austen’s novel which are spelled out more in the movie. In two hours and 16 minutes, many of the main plot points are included.

The producer, Lindsay Doran, loved Sense and Sensibility from the time she first read it. She wrote that it had all the qualities that would translate into a good film: “wonderful characters, a strong love story (actually three strong love stories), surprising plot twists, good jokes, relevant themes, and a heart-stopping ending” (The Sense and Sensibility Screenplay and Diaries, 11).

As I read about the making of this movie, I realized that while movie making can use larger casts and much more realistic settings, there are also challenges. Not all the actors were on location at the same time. Scenes in a certain location had to all be filmed in a short time period, and weather was a major issue. Scenes with a certain actor had to all be filmed back to back, even if those scenes were separated by long time periods in the story.

Of course movie-makers can also redo scenes until they get them right. Actors in a play don’t get that opportunity. But, they are doing the play in chronological order so they have that synergy and continuity. And they have immediate audience feedback, so the play should improve night after night.

I also enjoyed a more recent film adaptation, the 2024 Hallmark Sense and Sensibility. Unfortunately it starts with the same incorrect assumption as the Belle Esprit play: both say “the law” requires that John Dashwood inherit Norland rather than his sisters. Actually, in the book, it was the earlier owner’s will that gave the estate to, first the girls’ father, and then to their stepbrother’s son. While many estates at the time were entailed on the male line, like the Bennets’ estate, Lady Catherine de Bourgh tells us “It was not thought necessary in Sir Lewis de Bourgh’s family,” so Anne would inherit Rosings. Not all estates were entailed to male heirs.

In any case, the costumes and homes in the Hallmark movie are lovely, though more opulent than they would have been for the characters in Austen’s novel. Many lines from the book are included, though sometimes in different contexts. In an hour and 24 minutes, they manage to include most of the characters and events. We see Marianne’s impulsiveness and Elinor’s carefulness and wisdom. Willoughby and Marianne have a picnic alone at the beginning of their acquaintance, which would not have been acceptable, and Marianne visits Colonel Brandon alone later.

Oddly, this version makes Edward the stepson of Mrs. Ferrars. Also, Colonel Brandon and Eliza’s story gets changed radically, as I see in most adaptations. I guess it’s too complicated to give the story from Austen’s book, in which Eliza is an heiress, whose inheritance is essentially stolen by Brandon’s father and brother.

Edward is not a clergyman in this adaptation. Col. Brandon offers him a home on his estate, rather than a job, which seems odd. But Edward is shown as an honorable man who keeps his promises. Marianne is not so excessive in her passions, so does not recognize her excesses in the end and repent.

To me, the heart of Sense and Sensibility is a message. Self-control, integrity, and honor lead to right behavior and true happiness. Selfishness, self-indulgence, and lack of restraint lead to harmful behavior and misery (such characters may get wealth, but not true joy). Some adaptations communicate these principles to an extent, while others focus only on the romances.

What do you see as the heart of Sense and Sensibility? What adaptations have you enjoyed?

Discover more from Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

jane Austen

LikeLike

I like the Emma Thompson version, of course, but also the later one adapted by Andrew Davies. The heart of the novel is all those things you said, and the first single word that comes up for me is restraint. For me an adaptation in which people just generally express their emotions is doing something else.

LikeLike

I agree with you completely about the message of S&S. Another message I get from it is self-centeredness vs. selflessness. Marianne is all about Marianne to the discomfort and even pain of her sister and everyone around her. Every time I read the book I just want someone to say, “Marianne, Galileo called. The universe does not revolve around you.”

LikeLike

Yes! Thank you both. I wrote an article about Faith Words in Sense and Sensibility: a Story of Selfishness and Self-Denial, that you may enjoy. https://jasna.org/publications-2/persuasions-online/volume-43-no-1/cox/

LikeLike

Sorry, that shouldn’t have come up as anonymous, but I’m not on my own computer. This is Brenda Cox.

LikeLike