by Brenda S. Cox

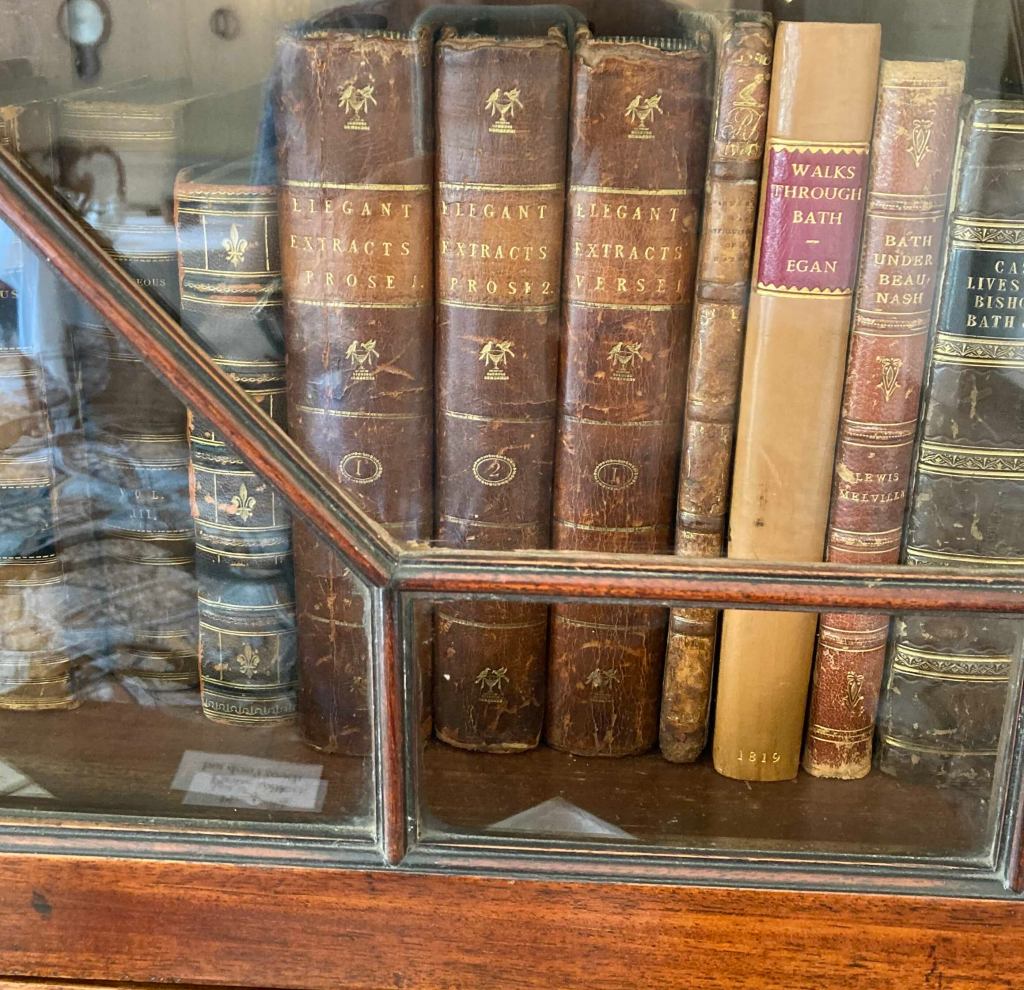

“Mr. Bennet was glad to . . . invite him to read aloud to the ladies. Mr. Collins readily assented, and a book was produced; but, on beholding it (for everything announced it to be from a circulating library), he started back, and begging pardon, protested that he never read novels.”—Pride and Prejudice, chapter 14

It’s hard to imagine a world without libraries. Even now, my Kindle shows me my “library,” all the books I have the privilege of owning or borrowing—probably far more than Jane Austen ever had the chance to read. My local public library lets me borrow books in print or digitally. I can even order books through inter-library loan from university libraries or other libraries around the country! We are blessed with amazing access to books. But what about in Jane Austen’s time? How did she and her contemporaries access books?

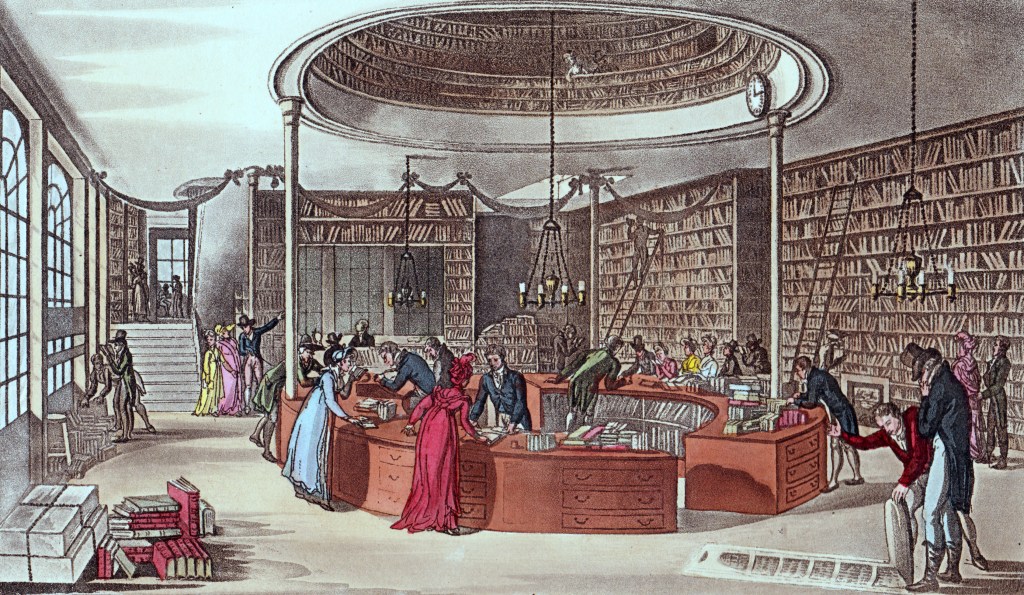

courtesy of British Museum, creative commons license.

Buying Books

In Austen’s England, buying books was prohibitively expensive for most people. We realize how wealthy Darcy was when we find that he is “always buying books” for his “delightful library at Pemberley,” “the work of many generations.” Bingley, on the other hand, with much less wealth, has so few books that he can fetch all of them for Elizabeth to choose from.

I just finished reading a fascinating article on “Circulation” of books, by David Allan, in Oxford’s English and British Fiction, 1750-1820 (details below), and I want to share some highlights with you throughout this post. It states,

“Most book-buyers, even by the early nineteenth-century, owned just a small handful, or at most a few dozen [books]—mainly because [of] the gulf between high retail prices and low personal incomes” (54). When Sense and Sensibility was published in 1811, it cost 15 shillings for the three-volume set. “The average Georgian reader . . . faced the prospect of parting company with an entire week’s wage,” having to choose between a new book and “a good pair of breeches” or “a month’s supply of tea and sugar” (54).

Austen’s father obviously prioritized books; he built up an extensive library of about 500 books. But in general, book ownership was for the wealthy. Even used books were prohibitively expensive for most people.

One solution was serialization. Newspapers and magazines would publish a novel bit by bit, or publish extracts from it, in their pages. Or a novel such as Robinson Crusoe might be published in small parts, for sixpence each, so it could be bought and read over time. Anthologies and abridged versions were also popular, intending to give the public a taste that might lead them to buy the whole book.

Lending Books

Those who owned books often lent them to others. In Austen’s novels, visitors enjoy the libraries of wealthier friends. In Sense and Sensibility, “Marianne, who had the knack of finding her way in every house to the library, however it might be avoided by the family in general, soon procured herself a book” (chapter 42). Jane Austen herself enjoyed her wealthy brother Edward’s library, writing to Cassandra, “I am now alone in the library, mistress of all I survey” (Sept. 23, 1813).

Literacy was spreading among the lower classes, partly due to the Sunday school movement which educated the poor on Sundays. Those with low incomes might buy cheap tracts; Hannah More produced “Repository Tracts,” subsidized by her rich friends, to give poorer people worthwhile, affordable reading material. Working-class people sometimes borrowed books from their employers or friends. Household servants might surreptitiously read from their employer’s library.

Religious Libraries

I was surprised to learn that the earliest libraries in England were associated with religious institutions. Cathedral libraries, “long established by this time” (58), allowed local people to borrow books, as long as those people were known to them or could get a recommendation. Authors Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Samuel Johnson borrowed books from cathedral libraries. Such libraries also offered magazines, such as the Gentleman’s Magazine and the Edinburgh Review, and sometimes novels.

Libraries were established in many church parishes to provide resources for country clergymen. These expanded into parish libraries that lent books to literate people of the parish. While they began with more theological texts, they added magazines and more modern literature such as novels in the 18th and 19th centuries. Dissenter chapels often offered libraries as well, supported by subscriptions from members and donations from the congregation. In 1809, a Wesleyan chapel library in Newcastle stated that most of their books were intended to teach “the fear of the Lord, which is the beginning of wisdom,” but the library would also accept “useful Books, containing nothing inimical to the interests of Religion” (60).

Book Clubs

From the 1750s on, “a veritable tidal wave” (60) of secular subscription libraries and book clubs began. Book clubs would buy a book, pass it around, then possibly sell the book once everyone had read it. Jane Austen was in such a book “society,” and mentions in her letters books they were sharing. On Jan. 24, 1813, she mentioned that Mrs. Digweed had one of the society’s books but obviously hadn’t read it, and it had been passed on to the clergyman’s family, the Papillons, who “like[d] it very much.”

Subscription Libraries

Some book clubs metamorphosed into subscription libraries. Other subscription libraries were established by professional groups or communities. These were supported by members’ initial fees and annual dues. Some were for specific topics or needs, such as scientific or literary endeavors, while others were more general. They tended to focus on nonfiction. In some subscription libraries of the time, though, 25-30% of the books in their catalogs are novels (61).

Circulating Libraries

The terms “circulating library” and “subscription library” were often used interchangeably. Both required paid subscriptions, and both circulated books. Technically, a circulating library was intended for the owners’ financial gain and was open to anyone who could pay. A subscription library was more limited and not for profit. But the boundaries blurred as time went on.

In the late 17th century, retail booksellers began adding options for customers to borrow books as well as buy them. By the mid-1700s, lending libraries were being set up as libraries, rather than adjuncts to bookstores. They often sold other goods and services, “ranging from printing and stationery to insurance, patent medicines, ornamental stonemasonry, and umbrellas” (64). We see this in Sanditon where the library offers “all the useless things in the world that could not be done without . . . many pretty temptations.” It also offers “numerous volumes” of books. Sir Edward Denham checks out a stack of five. He claims contempt, though, for the “mere trash of the common circulating library.” Many people of the time were concerned that novels would waste time as well as corrupt people’s morals, making them want to imitate the villains. Austen makes fun of this idea by creating Sir Edward whose goal is to become a great villain. Novels were still struggling to gain a good reputation in the world, as Austen discusses in Northanger Abbey.

By 1800 there were thousands of circulating libraries all around England. London had hundreds of them, while Bristol had at least 78. Some focused on novels, others on other types of literature. Most had some of both. Some circulating libraries were so large that they even published novels themselves.

A library started in the tiny town of Steventon in 1799. Jane wrote to Cassandra,

“I have received a very civil note from Mrs. Martin, requesting my name as a subscriber to her Library which opens the 14th of January, & my name, or rather Yours is accordingly given. My Mother finds the Money. Mary subscribes too, which I am glad of, but hardly expected. As an inducement to subscribe, Mrs. Martin tells us that her collection is not to consist only of Novels, but of every kind of Literature, &c &c. She might have spared this pretension to our family, who are great Novel-readers and not ashamed of being so; but it was necessary, I suppose, to the self-consequence of half her Subscribers” (Dec. 18, 1798).

In Mansfield Park, we read that Fanny subscribed to a circulating library in Portsmouth, wanting works of biography and poetry to educate her sister:

“Fanny found it impossible not to try for books again. There were none in her father’s house; but wealth is luxurious and daring, and some of hers found its way to a circulating library. She became a subscriber; amazed at being anything in propria persona, amazed at her own doings in every way, to be a renter, a chuser of books! And to be having any one’s improvement in view in her choice! But so it was. Susan had read nothing, and Fanny longed to give her a share in her own first pleasures, and inspire a taste for the biography and poetry which she delighted in herself.”—Mansfield Park, chapter 40.

Circulating libraries made books affordable for even those with little money, like Fanny Price (whose “wealth” was £10, for her three months’ visit). Some libraries, though, cost as much as 5 guineas a year. The standard annual fee was about twice the price of a 3-volume novel, ranging from half a guinea in the 1750s to two guineas in 1814. Most patrons could borrow two books at a time, only one of which could be a new book. They could keep a new book for two to six days, other books for a month. Fees were charged for overdue books. Some sent books to subscribers outside of town, who could borrow more books for a longer time, but had to pay shipping (Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature).

These prices were affordable for middle and upper-class patrons. But some libraries offered short loans for just 2 pence a volume, for those who could not afford subscriptions. Library loans were key to the personal, social, and occupational development of people of all levels of society.

David Allan concludes,

“The circulation of texts . . . provided ample opportunities for sociability, for the cultivation and display of politeness, and even for genuine philanthropy” [as wealthier people supported libraries for the benefit of others]. They also gave people opportunities for “self-improvement, for personal education, and . . . deep inward satisfaction” (68).

Novels, including Jane Austen’s, were a significant part of this process.

How have libraries, or easy access to books, impacted your life?

Sources

“Circulation,” by David Allan, chapter 3 of English and British Fiction, 1750-1820, edited by Peter Garside and Karen O’Brien, Volume 2 of the Oxford History of the Novel in English, pages 53-69. Oxford University Press, 2015. Parenthetical page numbers above are from this textbook.

“Circulating Library,” Wikipedia, for the difference between circulating and subscription libraries.

“Circulating Libraries,” Edward Jacobs, The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, edited by David Scott Kastan, Oxford University Press, 2006. Free online article.

Further Reading

“Going to the Library in Georgian London,” Jane Austen’s London

“The Temple of Muses,” Random Bits of Fascination

“The Circulating Library,” Sarah Murden, All Things Georgian

“Circulating Library and Reading Rooms, Bath,” Painted Signs and Mosaics.

Discover more from Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Loved the history of libraries. Claire Bellanti has a talk on topic too. There’s a book (not at hand) about how early Irish monasteries seeded European libraries with lost classical works.

LikeLike

Brenda, I commented, but it shows as anonymous. Maybe because I’m on road w phone.

Sent from my T-Mobile 5G Device

Get Outlook for Androidhttps://aka.ms/AAb9ysg

LikeLike

Thanks, Collins! This actually came out of research I’m doing for the novel I’m working on. One scene takes place in a circulating library in Bath. 🙂

LikeLike