By Brenda S. Cox

“As the clergy are, or are not what they ought to be, so are the rest of the nation.”–Jane Austen, Mansfield Park

What happened to the English clergy after Jane Austen’s time? Anthony Trollope, a popular Victorian novelists, wrote about the clergy of his time. I’m occasionally asked what I think of Trollope, since I write about the church in Jane Austen’s England, and Trollope wrote about England’s church and clergy around fifty years later, in the Victorian era. I confess that I have found the few Trollope novels I read rather slow, though I am planning to try again.

But I came across Trollope’s interesting book from 1866, called Clergymen of the Church of England. (Queen Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901, so this is the middle of her reign.) It’s not a novel, but a series of essays, partly serious and partly humorous, on the clergy of his time.

Jane Austen shows us some of the internal issues faced by the church in her day. Clergy saw their work as a job rather than a calling. Different levels of clergy received hugely unequal salaries, ranging from the riches of an archbishop to the literal poverty of the country curate. The system of patronage meant that livings could be sold to the highest bidder or given to the closest relative of the patron. Clergymen might hold multiple livings, either to make enough money to survive, or from greed. My book, Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England, explores these issues in detail in chapters 16 and 17, showing how Austen addresses them.

In Trollope’s Clergymen of the Church of England, he explores the position of clergymen about fifty years after Austen’s death. Some reforms had taken place, but in Trollope’s view, not nearly enough. The whole book is humorous and intriguing, but here are a few of his main points.

Archbishops

He starts at the top of the church hierarchy with archbishops, who he says were awe-inspiring “princes” not long before, but no longer. They are still high-ranking noblemen, with the Archbishop of Canterbury ranking above all non-royals in Parliament, just above the Chancellor and the Archbishop of York. They were venerated, wealthy, and lived in palaces.

However, at this point the archbishops were given a salary rather than income from property, so their incomes were lower. They stopped wearing wigs, which made them less impressive, and no longer venerated.

But they still had independent power. They were to appear to be guiding and controlling the church and clergy, without actually exercising that power. They needed to be moderate and good at peacemaking. The archbishop should defend the church’s doctrine in general, but not get involved in disputes on specific points.

“To carry an archbishop’s mitre successfully under such circumstances requires much diligence, considerable skill, imperturbable good humour, and undying patience.”

Trollope says that the archbishops of recent years have been such men, and everyone appears to be pleased with them.

Bishops

The situation with bishops was similar, except that there were many bishops and so, appropriately, there were varieties among them, high church and low church, those preferring formal worship and the Evangelicals.

Old school bishops, who wore wigs and were venerated, were “wealthy ecclesiastical barons” who amassed fortunes and lived like lords. Some had great political power. They obtained their posts in several ways: as scholars of classical Greek; as tutors of noblemen’s sons, who gained political power; as friends of royalty; and as advocates for political causes. However these bishops didn’t accomplish much. They didn’t start new churches, repair old ones, or stop the spread of Dissenters.

Trollope gives us a glimpse into stories of bishops from Austen’s time and before: “There were the old bishops who never stirred out, and the young bishops who went to Court; and the bishop who was known to be a Crœœsus [very rich], and the bishop who had so lived that, in spite of his almost princely income, he was obliged to fly his creditors; and there was the more innocent bishop who played chess, and the bishop who still hankered after Greek plays, and the kindly old bishop who delighted to make punch in moderate proportions for young people, and a very wicked bishop or two, whose sins shall not be specially designated. Such are the bishops we remember, together with one or two of simple energetic piety. But who remembers bishops of those days who really did the work to which they were set? . . . It is almost miraculous that the Church should have stood at all through such guidance as it has had.”

Trollope says the bishop of his day is a “working man.” He credits this to the Oxford movement which began thirty years earlier, stirring up the country to stronger religious feelings and challenging the clergy and bishops to more serious work. He admits that they also ran “after wiggeries and vestments and empty symbols,” but more importantly that they “built new churches, and cleansed old churches, and opened closed churches.” He says they also inspired the Low Church with their energy.

The bishop of Trollope’s day was no longer a scholar, but was generally an exemplary parish clergyman, often a “Low Church” Evangelical rather than a “High Church” follower of the Oxford movement. He now received 5,000 pounds a year (or less if his diocese provided less than that previously). So bishops were not longer as “picturesque,” and could be seen hailing cabs (drawn by horses) and walking home after ordinations.

However, bishops could still assign many church livings. They were restricted from assigning multiple livings to one person. But they did not have to assign them according to the needs of the parishes. Trollope wrote that the bishop, “still gives, and is supposed to give, his best livings to his own friends. . . . A bishop’s daughter is supposed to offer one of the fairest steps to promotion which the Church of England affords.”

The Civil Service, Army, and Navy, hadcleansed themselves of such nepotism. But in the Church, the bishop still believed it was his right to give out livings to his friends.

The Cathedral Dean

Trollope claims that no one quite knows what a dean does. Earlier he supervised the “chapter,” including “canons, precentor, minor canons and choristers,” kept the cathedral under repair, and made sure the services were glorifying to God.

But now, Trollope says, “We use our cathedrals in these days as big churches, in which multitudes may worship, so that, if possible, they may learn to live Christian lives. They are made beautiful that this worship may be attractive to men, and not for the glory of God.”

But now the deans receive 1,000 pounds a year, a comfortable, old-fashioned dwelling, time to focus on books, and a good place in local society. He is academically inclined, and keeps up some of the beauty and glory of the past in his peaceful Cathedral “Close.” When a new dean is needed, the Prime Minister tells the chapter who to choose, and they obediently vote for him.

Trollope appreciates the beauty of this tradition, saying, “Deans and chapters, though they exist with a mutilated grandeur, for the present are safe; and long may they remain so!”

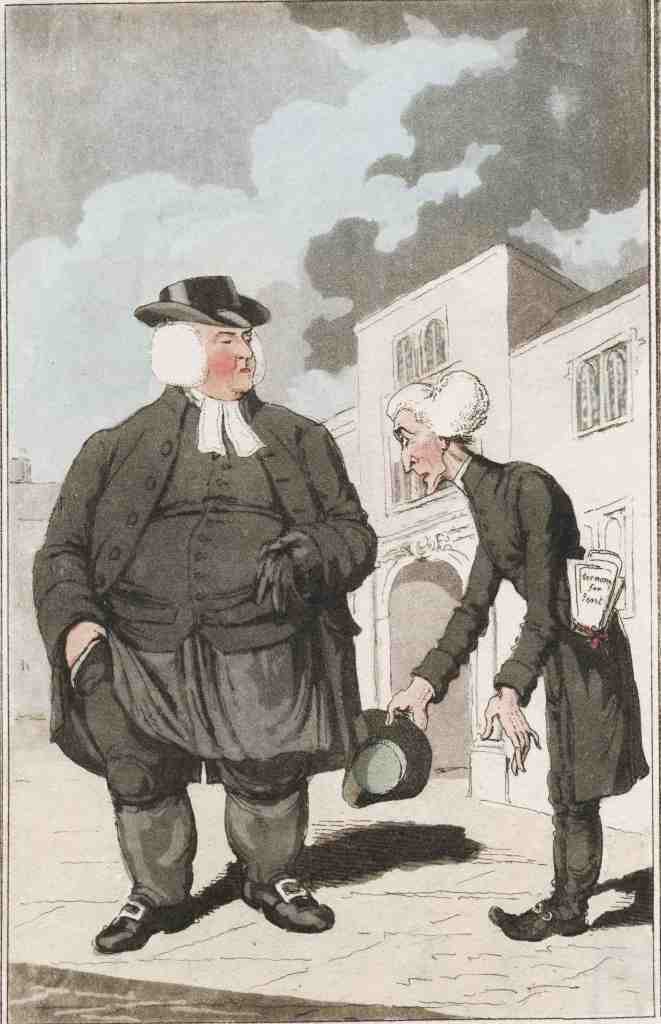

“A Was Archbishop with a red face,

B Was a Bishop who long’d for his place.

C Was a Curate, a poor Sans Culotte,

D Was a Dean who refus’d him a Coat

Even grudged him small beer to moisten his throat.”

© The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

The Archdeacon

“A dean has been described as a Church dignitary who, as regards his position in the Church, has little to do and a good deal to get. An archdeacon, on the other hand, is a Church dignitary, who in diocesan dignity is indeed almost equal to a dean, and in diocesan power is much superior to a dean, but who has a great deal to do and very little to get.” Trollope says that traditionally in the established Church, those with high income had few responsibilities, and those with low income had many responsibilities.

Archdeacons weren’t paid, but the bishop made sure they had livings that provided for them. In Trollope’s time they just had one good living each, though formerly they would have had several. Most had private means as well (gentlemen with property), which was part of the reason they were chosen.

The archdeacon held courts and made visitations to church parishes every 1-3 years. He was very familiar with his clergy’s lives. He made sure their churches were in good repair, and looked into scandals reported by churchwardens, though not very closely. Most archdeacons were not promoted, as they were just known in their own area. This is much as archdeacons were in Austen’s time.

To advance, they might sit in Convocation, which Trollope describes as “a mere debating society.” They no longer advanced by publishing books of sermons, because, Trollope writes “Sermons are not read now as they were some thirty or forty years since.” Certainly they were very popular in Austen’s time, but less popular apparently for the Victorians.

The archdeacon’s main place to shine was in his own rectory. “He is the very chief among parsons; and as the country parson—the country parson with pleasant parsonage, pleasanter wife, and plenty of children—is the true and proper type of an English clergyman, to which bishops, deans, canons, and curates are mere adjuncts and necessary excrescences, so is the archdeacon the highest type of the country parson.” Almost always married, necessarily a gentleman, he led the clergymen and society around him.

The Parish Parson

Trollope says the word “parson” has become old-fashioned, but it came from the word “person,” designated the parish clergyman “as the palpable and visible personage of the church of his parish,” making the idea of “church” visible.

Trollope wrote that a parson was “above a vicar,—who originally was simply the curate of an impersonal parson, and acted as priest in a parish as to which some abbey or chapter stood in the position of parson.” Now it is often a layman who gets most of the tithes, while the vicar gets the small tithes. A rector, who “had not only the full charge of his parish, but the full benefit derivable from the tithes,” was originally called a parson. “Rectors and vicars at present hold their livings by tenures which are equally firm, and they have done so now for more than four hundred years.” He says the rector is more like wine and the vicar more like beer. But both are parish parsons. They are like the captain of a ship, while a curate is a lieutenant. The parson was always a gentleman, almost certainly educated at Oxford or Cambridge. In Georgian times, “the parson in his parsonage was as good a gentleman as any squire in his mansion or nobleman in his castle.”

However, in Trollope’s time, theological colleges were training new parsons, qualifying men who were “less attractive, less urbane, less genial,—in one significant word, less of a gentleman” than before. And thus, according to Trollope, the upcoming Victorian parson was not as well respected or obeyed by country people as the parson of Austen’s time had been.

However, most parsons of his day were still gentlemen, Oxford or Cambridge graduates, often the second son of a squire or son of a parson. The knew country life, good and bad, and stood up against “gross profligacy and loud sin” but made compromises with “the peccadilloes dear to the rustic mind . . . with a little drunkenness, with occasional sabbath-breaking, with ordinary oaths, and with church somnolence.” Here is how Trollope described most country parsons of his day:

“[The parson] does not expect much of poor human nature, and is thankful for moderate results. He is generally a man imbued with strong prejudice, thinking ill of all countries and all religions but his own; but in spite of his prejudices he is liberal, and though he thinks ill of men, he would not punish them for the ill that he thinks. He has something of bigotry in his heart, and would probably be willing, if the times served his purpose, to make all men members of the Church of England by Act of Parliament; but though he is a bigot, he is not a fanatic, and as long as men will belong to his Church, he is quite willing that the obligations of that Church shall sit lightly upon them. He loves his religion and wages an honest fight with the devil; but even with the devil he likes to deal courteously, and is not averse to some occasional truces. He is quite in earnest, but he dislikes zeal; and of all men whom he hates, the over-pious young curate, who will never allow ginger to be hot in the mouth, is the man whom he hates the most. He carries out his Bible teaching in preferring the publican to the Pharisee, and can deal much more comfortably with an occasional backslider than he can with any man who always walks, or appears to walk, in the straight course.” He preaches, demanding a high standard, knowing that he won’t get it but must be satisfied with what he can get, and living at that lower standard himself.

“Such is the English parish parson, as he was almost always some fifty years since, as he is still in many parishes, but as he will soon cease to become. The homes of such men are among the pleasantest in the country, just reaching in well-being and abundance that point at which perfect comfort exists and magnificence has not yet begun to display itself. And the men themselves have no superiors in their adaptability to social happiness. How pleasantly they talk when the . . . outward world is shut out for the night! How they delight in the modest pleasures of the table, sitting in unquestioned ease over a ruddy fire, while the bottle stands ready to the grasp, but not to be grasped too frequently or too quickly. Methinks the eye of no man beams so kindly on me as I fill my glass for the third time after dinner as does the eye of the parson of the parish.” We can envision Henry Tilney or Edward Ferrars as becoming just such parsons as they age.

The Town Incumbent

Any clergyman holding a living is an incumbent. But the word, by Trollope’s time, was more often used for the clergyman of a church in a town, usually an industrial town. He didn’t receive tithes, but got money from renting out seats in the church (pew rents). This means he needed to be a compelling preacher, saying what people wanted to hear, in order to draw in people to listen and pay. He did not have the respected position of a country parson, and often didn’t know the people of his church well. Most town incumbents did not make a decent living.

In contrast, the country parson can do and say what he thinks will benefit his parishioners, as he knows them and his position is secure.

The College Fellow Who Has Taken Orders

The fellow of a college at Oxford or Cambridge could be ordained, and might be required to be ordained as a clergyman. Many of them, as they got older, gave up their fellowships, married, and took a country living as a “real” clergyman. Trollope thought it wrong that these men were “clergymen” for so many years without performing any church duties. They need edto be trained by working as curates under regular clergymen instead of by being in colleges.

The Curate in a Populous Parish

The problem of clergymen not being paid in accordance to the amount of work they did continued from Jane Austen’s time to Trollope. Trollope wrote, “It is notorious that a rector in the Church of England, in the possession of a living of, let us say, a thousand a year, shall employ a curate at seventy pounds a year, that the curate shall do three-fourths or more of the work of the parish, that he shall remain in that position for twenty years, taking one-fourteenth of the wages while he does three-fourths of the work, and that nobody shall think that the rector is wrong or the curate ill-used!”

Some progress had been made, in giving bishops a salary, and supplementing the income of some town clergymen.

The number of curates was increasing with the population; the number of rectors and vicars couldn’t be changed. Curates were no longer automatically considered gentlemen.

Victorian curates, like those of Austen’s era, came from Oxford and Cambridge, ordained at age 24. It was new that they felt a “special vocation” for ministry. They became curates at 70 pounds a year, but in a few years realized this was not enough to live on, and become miserable. The system needed to change.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Trollope went on to talk about the Beneficed Clergyman in Ireland, who had to contend with Catholic opposition, and modern clergymen who questioned many basics of the faith.

Clergymen of the Church of England shows that most of the issues of Jane Austen’s church lingered on through the Victorian era, but some reforms were being made. There were still great discrepancies between parishes, and between curates, vicars, and rectors, which were unfair. People still got church livings on the basis of personal connections rather than merit. Pluralism (holding multiple livings) had been eliminated, and the excesses of archbishops and bishops had been decreased. Many church leaders were more serious about their faith and responsibilities, while others were abandoning church teaching. More sweeping changes were made later, in the 20th centuries.

What do you think are the biggest issues facing today’s church in your country?

Further Resources

A discussion of Trollope’s religious views

A free copy of Clergymen of the Church of England

Timelines including Austen, Trollope, Dickens, and major events of their times

Satirical Cartoons on Jane Austen’s Church of England

Richard Newton’s Clerical Alphabet cartoon