By Brenda S. Cox

Jane Austen, when questioned about whether her characters were based on real people, “expressed a dread of what she called such an ‘invasion of social proprieties’. She said that she thought it quite fair to note peculiarities and weaknesses, but that it was her desire to create, not to reproduce; ‘besides,’ she added, ‘I am too proud of my gentlemen to admit that they were only Mr A. or Colonel B.’”—A Memoir of Jane Austen, by James Edward Austen-Leigh, chapter 10

Do you ever wonder where Jane Austen got her story ideas? Her characters and plots weren’t copied directly from life. However, she must have been a keen observer who took what she saw and heard and wove it together or elaborated on it to create her stories.

Her mother’s wealthy Leigh family was one source of such ideas. On the JASNA Summer Tour in July, I met Victoria Huxley, who lives in Adlestrop. Austen had relatives there whom she visited three times over the years. Ms. Huxley’s book, Jane Austen & Adlestrop: Her Other Family, tells some of their stories, alongside quotes from Austen’s writings that parallel the stories. (US link for the book) Let’s consider some events in the Leigh family that might have been echoed in Jane Austen’s novels.

Inheritance Plots in Austen’s Novels

“Mrs. Knight is kindly anxious for our good, and thinks Mr. L. P. (Leigh Perrot) must be desirous for his family’s sake to have everything settled. Indeed I do not know where we are to get our legacy, but we will keep a sharp look-out.”– Jane Austen, Letter of June 30, 1808

Jane Austen’s plots often involve inheritance. Pride and Prejudice revolves around the entailment of Longbourn to a male relative, leaving the daughters potentially impoverished unless they make good marriages. In Sense and Sensibility, this actually happens. Norland Park is bequeathed to a male heir, John and Fanny’s son, leaving the women with minimal incomes. In Persuasion, Sir Walter’s estate is entailed on Mr. William Elliot, and the family hopes he will marry Elizabeth and provide for them. Inheritance laws play a more minor part in Northanger Abbey, where Isabella Thorpe expects that John Morland, the eldest son, will have a much larger income than he does. In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford wants Edmund to become the heir, not the spare.

Inheritance in Austen’s Family and Sense and Sensibility

Jane Austen knew about the complexities of inheritance from her own family. Her brother Edward was brought in to continue the Knight line when that family had no male heirs. (He was not exactly “adopted,” but was made the heir.) When another branch of that family sued him, he had to pay them off.

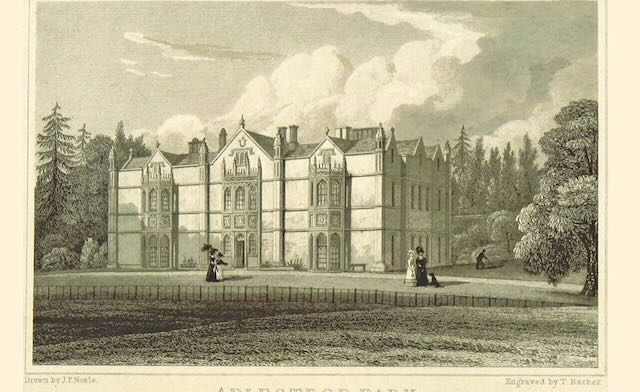

A more complex situation happened with Stoneleigh Abbey. There were two main lines of the Leigh family. One line inherited Adlestrop and the lands around it. The other inherited Stoneleigh and its lands, which became much more lucrative. Over the years, the Stoneleigh estate was inherited by male relatives of the original line, until that line died out.

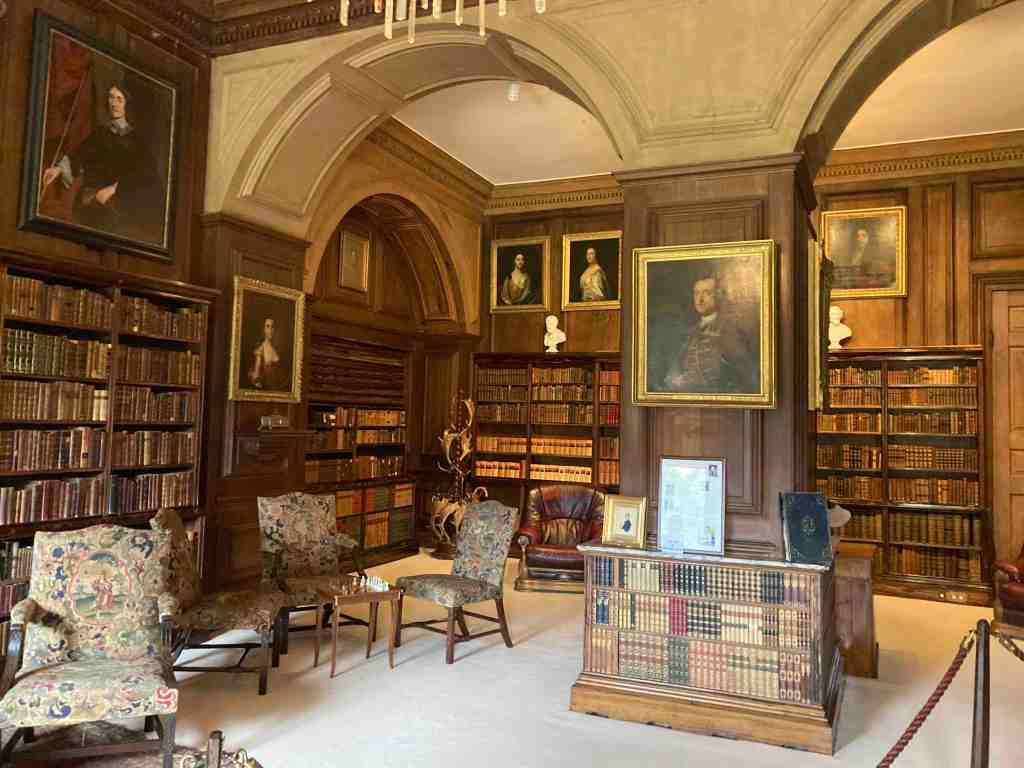

Edward, the fifth Lord Leigh, had inherited the Abbey in 1749 at age seven, and made many improvements once he came of age. He was a scholar and a gifted young man, apparently, but by 1767 was experiencing bouts of madness. He was officially declared a “lunatic of unsound mind,” unable to manage his estate, at age 32. He had made a will much earlier, while still sane. He left all of his mathematical instruments and most of his extensive library to Oriel College at Oxford. His sister Mary had a “life tenancy” of the estate after he died in 1786; she lived 20 more years, without children.

Her brother had named the heir, after Mary, as “the first and nearest of my kindred being male and of my name and blood that shall be living at the time of my determination of the several estates.” This was rather vague. Three claimants* from the Adlestrop Leighs were possible heirs to the very rich estate: Rev. Thomas Leigh, rector of Adlestrop; his nephew James Henry Leigh, squire of Adlestrop; and Jane Austen’s uncle, James Leigh Perrot (the name Perrot had been added to get him an inheritance through his wife’s family).

The eldest of the claimants, Rev. Thomas Leigh, took the estate; Jane and her mother and sister happened to be with him when he moved in, and they were very impressed by the Abbey. Rev. Leigh held it in trust for his nephew James Henry, who inherited it when Thomas died. James Leigh Perrot, who was already quite wealthy, also demanded a share of the inheritance. After the reading of the will, “James took away papers from this meeting to consult with his wife on the matter while also proudly stating that he was rich enough and hardly needed any increase in his fortune, but he still held out for a huge annual payment in exchange for giving up any claim to the estate” (Jane Austen and Adlestrop, p. 121). Leigh Perrot wanted £20,000.

He eventually would receive an annuity during the lives of the Perrots, with the full sum to come when James Henry succeeded to the estate. In making this agreement, “The Reverend Leigh took into consideration, ‘from my regard to Leigh Perrot and for the Cooper and Austen families, & to ensure to Mr. L.P. the means of better providing for them who are so very numerous’” (121). “It appears that both the Coopers and the Austens were given the impression by the Leigh Perrots that they would pass on any money that came to them and this was certainly what the Reverend wanted. Joseph Hill [the solicitor] endeavoured to ensure that the Leigh Perrots should give £8,000 out of the £20,000 to ‘Mrs. Austen’s family and Mr. Cooper’s’ but Mr. Leigh Perrot only promised that ‘he would make such provision himself, as he thought proper.’”

In other words, the money was given to James Leigh Perrot partly so that he could provide for his poorer relations, the Austen family and their cousins, the Coopers. However, at that time, the wealthy Leigh Perrots did not pass on any of the Stoneleigh money to the Austens or Coopers. “Jane put the blame at her aunt’s door” (in a letter of Nov. 20, 1808) (123).

This is similar to the story of Sense and Sensibility, where John Dashwood promises to provide for his sisters, but his wife talks him out of it. At one point, James Leigh Perrot complains in a letter that his money is not being paid to him, and that they have even stopped sending him game: partridges, pheasants, and hares. This is reminiscent of Fanny Dashwood saying they should send Elinor’s mother “presents of fish and game, and so forth, whenever they are in season.” As it turns out, Sir John Middleton sends such presents to Elinor and her family, not John Dashwood.

When James Leigh Perrot died in 1817, the Austens and Coopers hoped that their long-expected legacies from the Stoneleigh money would come at last. The Austen and Knight families were especially struggling financially due to the collapse of Henry’s bank and a suit against Edward for his estate. Leigh Perrot did pay money for sureties for Henry’s bank. However he left the rest of his substantial property to his wife for her lifetime. After her death, bequests were to be paid to any surviving children of Mrs. Austen, with the residue to James Austen and his heirs. She did not die until 1836, so Jane and James, who had died much earlier, did not benefit. Jane Austen was so upset by her uncle’s will that she had a relapse of the illness that took her life before long. The Coopers were also disappointed; Edward Cooper wrote Jane a letter expressing his deep hurt that he was excluded from his uncle’s will.

Jane and Edward’s anger over their loss of any legacy makes sense to me now that I realize that promises had been made that the Leigh Perrots would take care of the Austens and Coopers. Their great uncle had intended for them to receive a share of the huge Stoneleigh estate, but the end story was much like Sense and Sensibility, where the Dashwoods never did get what John Dashwood had promised.

The Leigh Family and Mansfield Park

James Henry Leigh, squire of Adlestrop, married the teenage daughter of Lord Saye and Sele, Julia Twisleton, in 1786. Julia’s family was full of drama. Her father committed suicide in 1788, a hugely shameful act in Georgian society. Her older brother met a beautiful young lady when they were acting together in an amateur play (called Julia), like the one in Mansfield Park. A few months later they eloped to Gretna Green, as Julia Rushworth did in Austen’s novel. The younger sister of the Twistleton family also eloped, then committed adultery and was divorced; Jane Austen mentions seeing her at a ball, calling her “an Adultress . . . [who] looked rather quietly and contentedly silly than anything else.” So perhaps we find echoes of these family events in Maria and Julia Rushworth of Mansfield Park.

There is also much discussion of “improvements” in Mansfield Park. Mr. Rushworth intends to call in Humphry Repton to make improvements at Sotherton, and Henry Crawford and Edmund Bertram discuss improvements to Edmund’s parsonage and glebe lands at Thornton Lacey. Rev. Thomas Leigh made similar improvements to his parsonage and land at Adlestrop, and at Stoneleigh Abbey once he inherited it. Repton was involved in both. I’ll give more details later.

The Leigh Family and Persuasion

Two Leigh family stories find echoes in Persuasion. These are found in the History of the Leigh Family, compiled and written by Rev. Thomas Leigh’s wife Mary. She was his cousin, also a Leigh. (By the way, George Austen, Jane’s father, was the clergyman who married Thomas and Mary Leigh.)

Elizabeth Wentworth

Jane’s great-uncle, William Leigh of Adlestrop, had a sister-in-law named Elizabeth Lord, called “Aunt Betty” in the family. Betty came from wealthy parents. Her father willed each of his daughters £1000, in 1718, if they married with the permission of the executors of his will, which included their mother, Mrs. Lord. One daughter, Mary, married William Leigh, with her family’s permission.

The other sister, Betty, fell in love with a Mr. Wentworth. At first her mother, Mrs. Lord, gave permission for them to marry. Then she withdrew it because Wentworth had little money; she said she would give the couple nothing.

Wentworth was in the army, headed for France. The morning of his departure, Wentworth and Betty secretly met at the church and got married, parting at the church door. He went to France. During his absence, Betty refused multiple offers for her hand, which angered her mother.

According to the History, Wentworth returned, less than five years later, now Captain Wentworth. The Leighs (Betty’s sister and her husband), knowing Betty’s secret, invited him to their home. They introduced him to Mrs. Lord as Lord Colvain. She was “much charmed with his sense and politeness. After his departure, being asked how she would have liked him for her son, she replied, ‘Son Leigh, had Betty married such a man without fortune, I would have forgiven and commended her.’” When they told her the truth, she forgave Betty for her marriage, and “divided her fortune between her daughters.”

It’s not quite the same as Anne Elliot’s story, but pretty close—a forbidden love to a military man named Wentworth, who is constant to her.

The real Wentworth had an illustrious military career in various wars. He advanced to Lieutenant General, and ended as an ambassador to Turin, in Italy. He died in 1747, 27 years after their marriage in 1720. Since he spent most of those years overseas, it’s not clear how much time he and Betty had together. They had no children. Wentworth left money to a new Foundling Hospital, as well as considerable property to his wife. She became the family benefactor, who often helped out her Leigh relatives financially.

Retrenching

In another family story around the same time, William Leigh inherited Adlestrop Park (the manor) in 1724. He found that “crippling debts” had accrued to the property, and they were in danger of losing the estate. The family was quite large, and the income of the manor was only about £1300 a year. So, “Grandmother Leigh” suggested that they give up all the family income, take a minimal stipend sufficient for their support, and go live in Holland for a time. They left the curate of Adlestrop, Mr. Parsons, in charge of the estate, let out the house, and took on a plan of economy.

After living in Utrecht from 1727 to 1732, they were able to return to Adlestrop in a better financial position. It sounds much like Sir Walter Elliot’s attempt to “retrench” by letting out Kellynch and moving to Bath. I doubt, though, that Sir Walter and Elizabeth were as financially careful as the William Leigh family seems to have been. It is surprising that the Adlestrop Leighs did not seek financial help from their prosperous cousins at Stoneleigh Abbey. Perhaps the Adlestrop family wanted to stay independent, or perhaps they asked and were refused.

Jane Austen, of course, did not take her plots directly from any of these happenings among her mother’s family. However, knowing these stories probably gave her ideas which she developed in delightful ways to help form her wonderful novels.

Christians, like Jane Austen, believe that God uses the events in our lives as part of the bigger story of what He is doing on earth. Do you believe that? Can you see how things that have happened to you have turned out to be part of a bigger story?

Sources and Further Reading

Jane Austen & Adlestrop: Her Other Family, by Victoria Huxley. US Amazon link

The Story of Elizabeth Wentworth or “Aunt Betty”—Jane Austen’s Anne Elliot? By Sheila Woolf (obtained from Stoneleigh Abbey)

Stoneleigh Abbey by Paula Cornwell (obtained from Stoneleigh Abbey)

Jane Austen: A Family Record, 2nd ed., by Deirdre Le Faye

This is terrific Brenda! All those similarities to people in JA’s family are much more than coincidence! She mined it all, didn’t she? And gave us her opinion about it all with her wit and satire in stories that still remain universal. Excellent post!

LikeLike

Thanks, Deb! Surely much more than coincidence. It’s like seeing a sculptor’s raw materials and then seeing how she makes them into a masterpiece!

LikeLike

No too sure; the Prince Regent’s librarian seems like a definite inspiration for Mr Collins – but P&P predates Austen’s introduction to him!

LikeLike

Good point. But Austen knew many, many clergymen; she mentions over a hundred in her letters. So I suspect Collins is an amalgam of several!

LikeLike